What makes a great portrait?

15 February 2022

A good question which Paul Moorhouse of the National Portrait Gallery attempts to answer here: http://www.npg.org.uk/blog/what-makes-a-great-portrait.php with reference to the work by William Orpen:

This was painted in 1916 and Paul Moorhouse comments on the emotion captured by the artist at the time when the statesman was enduring the guilt of his involvement in the failed Gallipoli campaign.

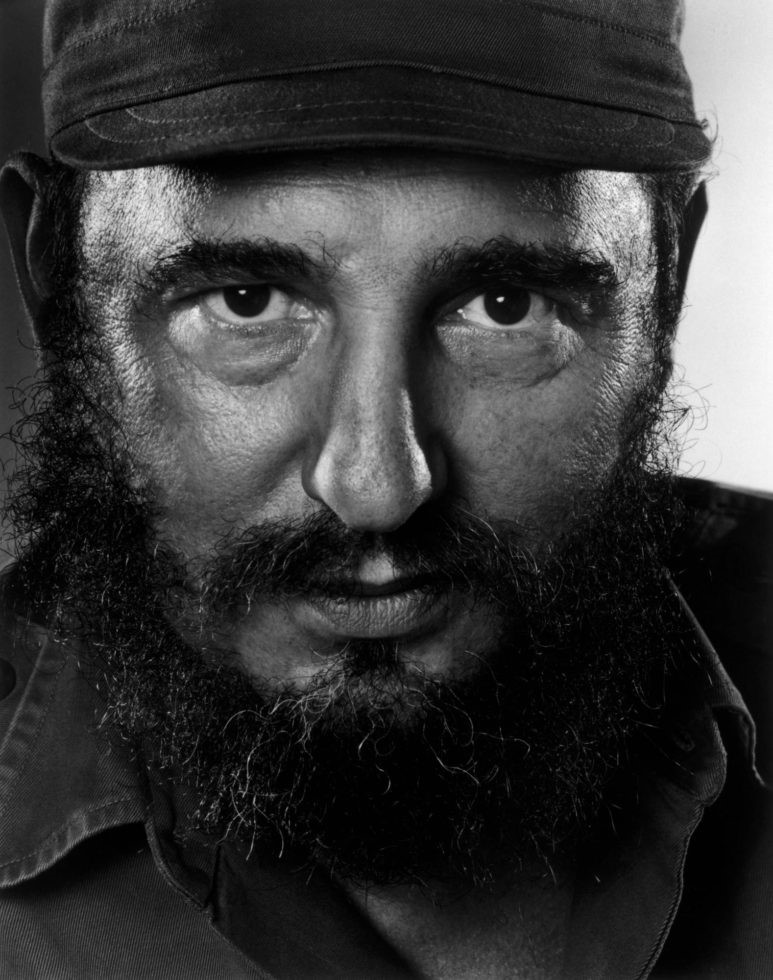

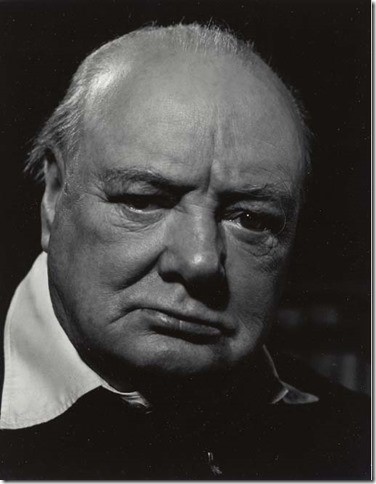

The pose can be compared to this photograph by Yousuf Karsh:

This was when the photographer famously plucked the cigar from the subject’s mouth and the look of annoyance is not hidden in the scowl on the face. But there is more to it than this. This was taken in 1941, in a much different phase in his career. Churchill was Prime Minister and leading the country in another conflict. His bearing is not humbled like in the Orpen work, but determined and defiant. Where Orpen pictured a defeated man, Karsh captured a man who would not and could not be beaten.

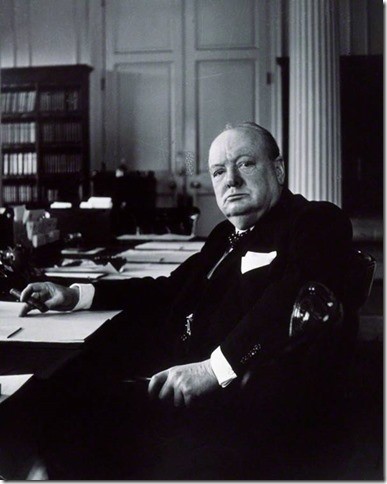

Cycle back a year to 1940, Churchill had just been accepted as Prime Minister on Chamberlain’s recommendation, the war with Germany was just beginning and Cecil Beaton captured this in the Cabinet Room at No 10 Downing Street.

The cigar is still there and the look is more relaxed. He is leaning back in his chair and the look in his face is more benign. But there is still the determination and the will to win. He is relaxed but confident and in control. It is interesting that the photographer chose to include a lot of clutter in the background. The previous two pictures were devoid of extraneous detail; one senses the chair is only there as a prop to lean against, but the Beaton picture has a lot of background. Perhaps he is trying to suggest an air of being busy, lots going on, a snatched moment in time. But the pose looks too considered and arranged.

History records that the allies won the war and that Churchill became one of the great war leaders. The pain of Gallipoli was erased and Churchill could smile. This is recorded by Alfred Eisenstaedt in 1951 when Churchill was back on the campaign trail, and ultimately back to No 10 as Prime Minister. I do not know if this shot was arranged or simply snatched while he was showing his signature V for Victory sign to his supporters. Nevertheless, the countenance contrasts with the previous pictures and we are left wondering whether this was another side to the man or whether it was a campaign smile for the benefit of onlookers.

Order was restored by Phillipe Halsman in the same year.

The dour, serious expression is back but there is not the determination that we saw in the war pictures. It has been replaced by an almost kindly appearance, as though he is about to break into a smile. This one is close cropped, there is no background or other props to place the picture into context, although it is evident that his style of dress is less formal.

Here are five pictures of Winston Churchill; they all say something different but they all say something. Through them we get a glimpse of who he was. In closing his National Portrait Gallery article, Paul Moorhouse says, “Though harrowing, Orpen’s portrait of Churchill is stamped with an unmistakeable and deeply affecting veracity of feeling. And that, for me, is one of the hallmarks of great art.” This conclusion comes after Moorhouse has described the historical context, “…Churchill was enduring the ignominy of blame for the deaths of 46,000 men. As First Lord of the Admiralty, responsibility for the disastrous Battle of Gallipoli was levelled at him. Demoted, Churchill resigned and submitted to a commission of enquiry.” This implies that to produce a great portrait the artist needs to show the great depth of emotion that arises from such a harrowing period.

By that criteria are the other pictures examples of great art? The Orpen work was produced at a time when the subject’s emotions were intense, possibly more so than at the times of the others, that gives Orpen a greater palette to work from but the other pictures all tell us something of the emotion that was being felt at the time. The Karsh portrait in particular has stood the test of time and become one of the most enduring and well-known pictures of the man.

I don’t know if it is an urban myth or whether uncivilised populations actually used to believe that the camera captured a part of your soul but that is what we should be striving for when photographing people; to pictorialise a part of their being, to bring something to print of who they are, perhaps to physicalise something spiritual. This is what makes a great portrait.